- Home

- Andrew Symeou

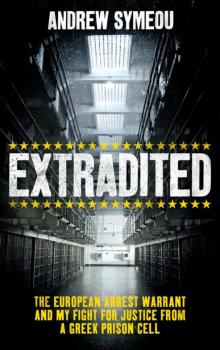

Extradited

Extradited Read online

* * *

CONTENTS

* * *

Title Page

Dedication

Note from the author

Part I

Chapter 1 – Sorry for my language

Chapter 2 – Maximum twenty years

Chapter 3 – Squash and roll

Chapter 4 – The investigation

Chapter 5 – The argument

Chapter 6 – The protest

Chapter 7 – The South Wales Police statements

Chapter 8 – Jacqui Smith

Chapter 9 – The hearing

Chapter 10 – The ruling

Chapter 11 – The strength

Chapter 12 – Walking the mile

Part II

Chapter 13 – Thinking of you

Chapter 14 – Day 1

Chapter 15 – Patras and Zakynthos

Chapter 16 – We need guns

Chapter 17 – Fifteen minutes

Chapter 18 – How to get high without drugs

Chapter 19 – Las Vegas

Chapter 20 – The tongue

Chapter 21 – Into the wild

Chapter 22 – A night to remember

Chapter 23 – The accused who punched the victim in the head

Chapter 24 – A mixture of madness

Chapter 25 – Time for school

Chapter 26 – It doesn’t matter how long it takes

Part III

Chapter 27 – Starred up

Chapter 28 – The King of the Greeks

Chapter 29 – An easy target

Chapter 30 – Waiting for exam results

Chapter 31 – A tranquil mishmash

Chapter 32 – Days of the week

Chapter 33 – Fed up

Chapter 34 – To fly or to fall?

Part IV

Chapter 35 – Does it have to be a pair of socks?

Chapter 36 – Or something like that

Chapter 37 – One hundred per cent

Chapter 38 – A clean-shaven male

Chapter 39 – Any blonde will do

Chapter 40 – Thumbs up, thumbs down!

Chapter 41 – The airport caterpillar

Chapter 42 – Think mode

Chapter 43 – Not worth the paper

Chapter 44 – And it will

Acknowledgements

Copyright

* * *

NOTE FROM THE AUTHOR

* * *

I wrote Extradited because it’s a story that needs to be heard. This isn’t just another ‘bleeding heart’ sob story of an innocent person behind bars (we’ve all heard that story before). One of my key motivations behind writing this book was to show by example how vulnerable British citizens currently are – it highlights why our government must make further changes to the controversial European Arrest Warrant (EAW). To those unaware of what the EAW is, it is a fast-track extradition system, which was enforced in the wake of 9/11 in an attempt to fight terrorism. It means that if authorities in other European countries are to issue a warrant for a British person’s arrest, Britain must send them to that country without considering any evidence at all. It is a clever idea in theory, as it is cheaper and quicker to extradite criminals – but there are barely any safeguards to protect innocent people from severe abuse (such as sloppy investigations, mistaken identity and pre-trial detention abroad). What happened to me could happen to absolutely anyone, and it’s difficult for people (especially those in government) to truly understand how flawed the EAW is without having been an innocent person caught in its trap. I also appreciate that an innocent young man lost his life in the summer of 2007. I have absolutely no connection to the events that led to his death, and I am completely sympathetic to his family, who experienced a grave tragedy. Our campaign was a fight for justice – and this is a fight for change.

To avoid confusion, I was charged with ‘fatal bodily harm’ (according to Greek law). In Britain the charge would have been manslaughter, but it was translated as either ‘murder’ or ‘manslaughter’ in different cases.

For Andreas Theodoros Pericleous

27 January 1932 – 5 October 2014

A Great Uncle

* * *

PART I

* * *

Violence is the last refuge of the incompetent.

– Isaac Asimov

1

* * *

SORRY FOR MY LANGUAGE

* * *

4 April 2013, the Coroner’s Court, Cardiff

I was sitting in a courtroom again, only this time it was on British soil. After spending two years of my life trapped in Greece and a further two years picking up the pieces, it was exhausting to be sucked back into the case again. My heart would have been palpitating at an extremely fast rate, but I was pumped up with prescription beta-blockers – a fantastic chemical invention.

Six years earlier, in 2007, I had gone on a two-week summer holiday to Laganas in Zante – the Greek island also known as Zakynthos. I was with seven of my best friends – ‘the boys’ – and the holiday was the usual mixture of sun, sea and nightlife. It was quite good fun, but nothing remarkable happened. We were just a group of normal eighteen-year-olds, and we were there to have a great time after completing our A levels. Thinking about it with hindsight, we were young and it was all very innocent.

While we were holidaying in Zante, a Welshman called Jonathan Hiles had tragically passed away after allegedly being attacked in a nightclub called Rescue. I didn’t know Jonathan and had never met him. An unknown male was said to have been urinating on a raised stage where Jonathan and his friends were dancing. Some time later, after an exchange of a few words, a punch was thrown. Jonathan fell from the stage head-first and died two days later in a Greek hospital from a brain haemorrhage – it was the day before his nineteenth birthday. I can’t even begin to imagine how devastating it must have been for his family.

The coroner for Cardiff, where Jonathan lived, was obliged to conduct an inquest into his death (even though six years had gone by and he had passed away abroad). I’d been summoned to appear as a witness, but I knew nothing of what had happened to Jonathan – we’d never crossed paths. During my time in Zante there had been no arguments, no fights – I didn’t see any violence at all. I wasn’t in the same building as Jonathan when he was struck. A full criminal trial had already taken place in Greece two years earlier and I’d been found innocent of his murder (fatal bodily harm according to Greek law). It unfolded that I was merely a random person from a photograph, which was taken on a different night from the attack.

It was Day 2 of the inquest and I sat on the second row of the public benches. My parents were sitting to my right, but we didn’t feel the need to speak. The three of us were far too involved in our own thoughts. The entire left wall of the courtroom was filled with journalists and reporters, sitting wide-eyed and ready to jot down as much information as possible.

Chris Kyriacou and Charlie Klitou had been summoned as witnesses too – they were schoolfriends of mine who were in Zante at the same time as my group. In the periphery of my vision I caught sight of them entering the courtroom, but I didn’t want to make eye contact. I hadn’t spoken to either of them since early 2009, the year that I was extradited to Greece. The victim’s dad sat to the right of the bench in front of us, the same row as the barrister we’d appointed. The room began to fill with the victim’s family and friends. It was silent but filled with tension; not even a whisper went unheard before the coroner entered. I’m sure that she was eager to discover how I had become the key suspect in the first place.

Chris was called to the witness box. He was still as skinny as ever, but he’d definitely grown since the last time I’d seen him. When he began to speak I noticed that his voice was d

eeper than I’d remembered. It was always slightly high-pitched and a bit yappy, but what I was hearing now was the voice of a man. It was a harsh reminder of how many years had passed since I’d been wrongfully accused of this crime.

He explained to the coroner that he and Charlie Klitou were on a different holiday package from my group. The two of them had decided to book the holiday later than us, and the only available dates for the same package fell four days after we would arrive, leaving four days after we would return to London. Overall, the two of them overlapped with us in Zante for ten days.

He continued his testimony by explaining that our group of friends had gone to a series of different bars and nightclubs on the night when Jonathan was allegedly attacked. According to witnesses, the event had taken place between 1 a.m. and 1.30 a.m. on 20 July 2007. At that time, we were in another bar, which was over 200 metres from the Rescue nightclub, where we stayed until around 4 a.m.

‘For the avoidance of doubt, did you at any stage that night, the 19th/20th, see Mr Symeou hit another person?’ asked the coroner.

‘No! And I’ve never seen him hit another person in my life,’ Chris exclaimed.

‘How long have you known him for?’

‘Since Year Seven, so since we were probably about twelve years old.’

Chris told the coroner that he and Charlie had stayed in Zante for four days after my group had left the island. On the second of those days, when I was back in London, Zante police officers had unexpectedly turned up at the hotel. The police were showing photographs taken by a professional photographer in the Rescue nightclub from a special event night (the night before the incident) and one of the photographs happened to be of my face on a crowded dance floor. Chris continued to explain that the hotel manager had recognised me from the photograph as a previous guest. Knowing that we were friends, the manager had sent one of the holiday reps to Chris and Charlie’s hotel room to inform them that the police wanted to see them for questioning. The officers seized both his and Charlie’s passports, took them to the police station and then sat them in separate rooms.

‘They asked me where my family was from; I said they’re Greek Cypriot. Instantly one of them turned to me and said, “You’re lucky your family are from Cyprus, or this would be a lot worse.”’

The coroner asked him if he could speak Greek, to which he replied that he could understand only key words or phrases.

‘They sat me down on a chair in the middle of that room, then turned all the lights off, then…’

The coroner interrupted, ‘So you were in darkness?’

‘Basically darkness, if you imagine a square room – there was some light coming through a glass window into the hallway every time someone opened the front door of the police station – otherwise it was basically darkness,’ he answered.

Slowly more and more policemen enter this room; in total there were probably six or seven of them. One of them was the chief police officer; another one did most of the hits and beatings. There were about four others, who I think were there just to intimidate me – just holding their batons like this.

He mimicked how the officers had stood on guard with their batons in two hands, ready to use them at any moment.

I was left to sit there for a while, which obviously made me quite scared. I had no clue what was going on or what was about to happen to me. This large police officer comes in; he was about 6ft 3in. or 6ft 4in. He was big, bald, shaved head … looked like he went to the gym all the time. He walks past the room, motioning as though he was washing his hands and was like, ‘I’m getting ready for you.’ That intimidated me completely. I was thinking, what is gonna happen to me here!? They said constantly, ‘You know what’s happened!?’ I told them, ‘I don’t know what happened!’ And I asked them, ‘What has happened!?’ But they wouldn’t tell me.

‘So at this stage do you know what this is about? Had Jonathan’s name been mentioned?’ asked the coroner.

‘No, I found out at about half ten that night, after about five hours!’

‘So you didn’t know it was about a boy who had died?’

‘No.’ He shook his head.

This large guy comes in the room, he did the majority of the questioning. I asked him, ‘What’s happened? Has there been an argument? Has someone stolen something? Has there been a fight?’ As soon as I said that word [fight], he just went ballistic! He grabbed me from my neck. At this time I was eighteen, I was even smaller than I am now. I think his hand fitted around my neck. He held me there and said, ‘You know what’s happened, tell us now!’ I’m in tears at this moment. They left me in the dark room for hours with no water. I could hear Charlie next door being hit. I could hear loud bangs and a lot of shouting. I could vaguely hear what they forced Charlie to say, which was that Andrew Symeou hit Jonathan Hiles. I glanced at the clock, it was about 12.30 a.m. when they let Charlie go. When they came back they kept on saying, ‘You know that your friend’s done it.’

‘Was there any doubt in your mind that Mr Symeou hadn’t done this?’ asked the coroner.

‘No doubt, no.’

‘You were absolutely sure that he hadn’t?’

‘100 per cent sure, yes, and every time I said the words “I don’t know what happened”, they would hit me.’

‘Where?’ the coroner asked softly.

Either a back hand round the face, or they would punch me in the side of the head. At one point they grabbed my head and smashed it against the wall. He told me that if I kept on saying that I didn’t know they would keep on hitting me. But I didn’t know – there was no answer that I could give! It got to the point where I thought, I know that Charlie had already said it was Andrew, even though he hadn’t committed the crime. My thinking was, I just have to do what they want me to do. My assumption was that I could instantly speak to someone at the embassy to sort this out.

Chris told the coroner that the officers slapped and punched him over a period of eight hours – they even threw a full bottle of water at his head. He was allowed to leave only once he’d signed a handwritten document, which was in Greek. He couldn’t understand what it said and a translator was present only at the start of the interrogation. The police officers sent her out of the room so that she wouldn’t bear witness to any more violence.

The document was written up already. It seemed like they had added one sentence on a piece of paper, [but] suddenly a whole document of writing came to me! They made me sign it. Now I know it said something about Jonathan and Andrew having an argument in a club over a girl, and then Andrew punched him. Once it was signed they told me I could leave. The young officer tried to shake my hand and said, ‘Sorry that we had to beat you.’ Who makes a comment like that after they have just beaten someone? Every time we go to court it seems like no one is listening, but this is what happened. Unfortunately, sometimes, it looks like this is what the police there do!

‘How old were you at the time?’ asked the coroner.

‘Erm … eighteen,’ he answered.

Charlie’s name was called and I heard him shuffling behind me before walking to the witness box. I noticed that he’d also grown since I’d seen him last. He was quite a good-looking guy with the same freshly cut hair that he’d always tried to maintain.

He told the coroner that when he and Chris were taken to the police station in July 2007, he was made to sit in another dark room for eight hours. The officers didn’t hesitate to slap and backslap him in the face; it seemed that his treatment was even worse than Chris’s. One of the officers threatened to strike him with an ashtray and a large officer entered the room with a police baton.

When he came in with that … sorry for my language … but I was crapping myself. As he came in he threw the interpreter out the room, then he came towards me and he was by my right side – but I couldn’t look at him. I wanted to look at him, but the other guy said, ‘You look at me in the eye!’ So I was looking at the guy in front of me.

Charlie received a powerful rig

ht-hook punch to the chin, which he later went to hospital for. The officers violently interrogated him about an event of which he knew nothing. ‘Whenever I would disagree or say no … they didn’t like that. They didn’t want me to say no,’ he said. ‘It came to the point when I cracked, they kept hitting me. I feared for my wellbeing and I didn’t know what was going to happen next.’

2

* * *

MAXIMUM TWENTY YEARS

* * *

I was born in 1988 and raised in Enfield, north London. Life began in Palmers Green – a leafy, suburban area, home to one of the largest populations of Cypriots outside of Cyprus itself. For that reason, I’d never really felt like part of an ethnic minority growing up. I’m of Greek Cypriot origin but both of my parents were born and bred in London, so we’re as anglicised as you can get.

Greek was hardly ever spoken in my household either. It’s unfortunate because I’ve always considered it to be such a great language – soft enough to sound pleasant to the ear, but abrupt enough to give emphasis to well-timed punchlines and sarcasm. Although Greek wasn’t spoken in my house, my grandparents would speak it all the time. The language would fly out of their mouths without them having to put in any effort. I definitely envied them it, even though they spoke it in its colloquial ‘Cypriot-village’ dialect. I attempted to learn modern Greek, but found the grammar to be complicated and difficult to grasp. At least I’d picked up the important key words and phrases, so I was fluent in what I’d call ‘Greenglish’ – English with the odd bit of Greek thrown in!

Extradited

Extradited